Through the fog

At 9 a.m., the air in Waynesville was a sweetly perfumed 60 degrees, and the

At 9 a.m., the air in Waynesville was a sweetly perfumed 60 degrees, and the

During the summer of 2011, billions of cicada eggs hatched inside tree twigs across the

Throughout the National Park Service’s 108-year history, countless people have made sacrifices, taken stands, and

This April, Smokies Life received national recognition at the 2024 Public Lands Alliance Partnership Awards

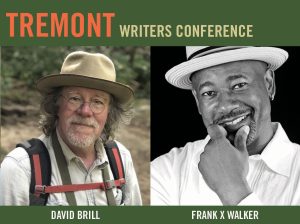

Frank X Walker and David Brill share a fascination with the Great Smoky Mountains. One

David Brill is one of the Smokies’ great living storytellers. Having contributed more articles to Smokies Life journal than almost anyone, he’s also published several book-length meditations on the paradoxically destructive and regenerative power of nature and the complex relationship with it we must all learn to navigate as humans. He considers himself a writer in the “outdoor-adventure” field, but his work doesn’t shy away from the contemplative, the quiet moments when wild places arouse in us feelings of solitude, solace, communion, and awe.

In November, Smokies LIVE published part one of an interview with Brill, conducted at the Lilly Pad Hopyard Brewery near Obed Wild and Scenic River on Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau. In this comfortable setting not far from his home—a remote cabin in the woods, whose construction he chronicled in the 2000 memoir A Separate Place—Brill opened up about his origins as a writer, his formative experience hiking the Appalachian Trail at age 23, and the philosophy that guides his approach to chronicling the natural world.

In part two of our conversation, we discuss his evolution as a writer, his latest book, Into the Mist, and what he’s working on next.

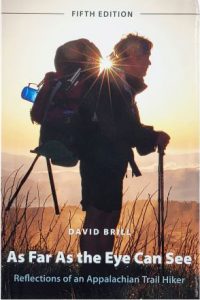

Smokies LIVE: In your first book, As Far as the Eye Can See: Reflections of an Appalachian Trail Hiker, there’s a moment that stuck out to me, when you’re crashing in a church in Monson, Maine. You meet an older gentleman, a tragic figure suffering from alcoholism. After witnessing his daily descent into intoxication, you write, “For the first time in my life I wondered what it would be like to grow old.”

That happened more than 40 years ago. Did you think you’d still be writing about nature all these years later? Did you have a sense of how your later life would unfold?

David Brill: From the perspective of a 23-year-old, it was difficult to imagine where my trail experiences might lead me. As it turned out, my months on the AT played a major role in shaping my career aspirations and determining how and where I would choose to live.

I found two entries in my journal years after the fact that were prescient. I wrote about how my great dream in life was to make my living as a writer. And I also expressed my desire to live in a cabin in the woods. I launched my writing career shortly after completing the trail, but it took me 20 years to get to the cabin.

I remember so vividly being in that church and being filled with pity and sadness over the older man’s condition. His circumstance was so starkly different from the energy and optimism that attended being young and on this footloose journey. But when I look at where I am now, I’m living the life I dreamed about all those years ago. I’m certainly not as spry as my 23-year-old self, but now, rather than retreat to the woods, I live in their embrace. I sit on my back deck, and I’m surrounded by nature. I’m glad I surrendered to those early desires and wound up where I did.

SL: It’s inspiring to see someone commit himself to writing 40 years ago and still be writing now. When you grow up wanting to be a writer, hanging out with writers, you see a lot of people drop out of it, go to law school, move on to other things. So, I find it impressive that you’re still writing today. How do you find the drive to continue producing new work?

DB: I reflect on this often. You know, early on, I worked my ass off. I worked so hard on every assignment I fielded. I was up sometimes two or three days without much sleep, agonizing over these articles. Every line, every word, the pacing, the rhythm—they had to be as close to perfect as they could be. And after submitting the piece, I would pace around the room, waiting for that call of affirmation from the editor.

The writing process became easier over time. There was still the fear of failure, trying to impress editors and give them exactly what they wanted. But I found—and still find—a great deal of joy and reward in the creative process.

I continue to love writing, and I can’t imagine doing anything else. Right now, I still have the energy and passion to sustain my work, but, at some point, I fear that my energy is going to start to ebb. And that’s going to be really hard.

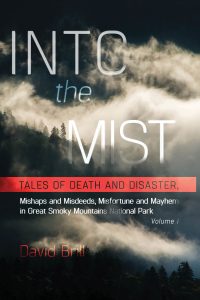

SL: I think a lot of writers share that fear. But your work has continued to evolve as you age, especially with your latest book, Into the Mist: Tales of Death and Disaster, Mishaps and Misdeeds, Misfortune and Mayhem in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. And I heard you’re working on a book for UT Press about the Manhattan Project and its lasting impact on East Tennessee. Is that right?

DB: Yes, I was the lead editor on an upcoming book, Critical Connections, about the history of the University of Tennessee’s partnership with Oak Ridge National Laboratory, beginning in the 1940s.

SL: It appears that lately you’ve turned more toward historical subjects. I wonder how that’s affected your work, if there was something that caused you to look more toward the past.

DB: Well, Into the Mist was commissioned. The editor of Smokies Life journal asked me to come up with a concept for that book.

Once I began writing about tragic fatalities and major weather events in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I was riveted by the incidents. Through the Freedom of Information Act, I was able to acquire the redacted incident reports for what would become the book’s 13 narrative chapters. And the park service staffers, the rangers and law-enforcement personnel, gave me all the additional information I needed. The raw material was already there in the detailed incident reports, and they provided a natural narrative structure. When I set out to write the first chapter about John Mink, who died of hypothermia on the Miry Ridge Trail in 1986, the story was there, begging to be told. In crafting the book’s chapters, I felt the same narrative drive I feel when I’m relaying my own outdoor experience: “Where do I start, what facts do I present, how do I hook this reader?”

SL: Into the Mist is a propulsive book; I flew through it. It seems like you have a good handle on how to tell these stories compellingly while remaining empathetic to your subjects. But I have to say, the chapters about crime investigations were especially engaging.

DB: The rescue stories were a joy to write. With the deadly derecho of 2012, which claimed two lives and injured dozens of individuals, and the blizzard of March 1993, which stranded 159 people in the park’s backcountry, the park service effectively rallied its partners and brought injured and isolated people to safety.

But the chapters that deal with death and crime were much more difficult to craft. I couldn’t turn away from the narratives, but the awareness that these stories were chronicling actual human lives challenged me emotionally. Most of my work has been about people having fun in the outdoors. So, Into the Mist was very different, but I loved the project. And I’m a bit more cautious out on the trail these days.

SL: In the introduction, you write about how the book “can be instructive, allowing GSMNP managers to assess the relative risks associated with various activities and specific locations within the park and thereby enhance visitor safety and education efforts.” I’m drawn to that idea of writing as a service, offering something that people can use.

DB: I would say that many, if not most, of the deaths chronicled in Into the Mist could’ve been prevented. If you don’t go in the water, you won’t drown. If you go out on a winter excursion, you should expect that you might hike into the teeth of a blizzard. Do you have shelter? Do you have a warm sleeping bag and multiple thermal layers? Do you have extra rations of food?

It’s interesting; when I’ve done book signings, there have been a few prospective readers who think I’m exploiting the suffering of people to turn a profit. That was not my intention at all. Many other readers, however, have kindly acknowledged how sensitively the subjects were treated. I really tried to bear in mind through the writing process that these are human beings, not just words on a page.

Throughout the writing of Into the Mist, I had the notion that these are tales that can heighten awareness of risk and showcase the extraordinary efforts of the park’s ranger staff to keep visitors safe. As for the latter, the story of John Peck, the fugitive who’d allegedly gunned down his girlfriend and headed to the park, is a case in point. That chapter depicts the efficiency and valor of the law-enforcement rangers in confronting an alleged killer and protecting visitors from harm. It builds confidence in the park’s rangers, exquisitely capable people who are devoted to safeguarding you and the millions of others who visit the park each year.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.